Jerry Brown’s “elegant density” development plans ignore needy Oakland neighborhood from notorious 60 Minutes story

New MacArthur BART Transit Village Plans Ignore the Shabby “West Side” Neighborhood

By Lauren Dockett

According to northwest Oakland resident Madeline Wells, when the MacArthur BART station was built nearly half a century ago it struck a “death blow to the community.” Recently the station had an opportunity to become the area’s redeemer.

Last month BART, along with private developers and Oakland city officials, unveiled plans for a MacArthur station transit village. The village, for which ground is set to be broken in 2003, is planned as a combination of new businesses and mixed-rate housing built around the station, and it’s a project that many in the community had once hoped would help to revitalize the surrounding neighborhoods. But now a decision to develop only on the east side of the station means the village may have only minimal impact on the neediest areas.

In effect, says Wells, the station will still have “its back to a black neighborhood.”

The neighborhoods to the west of BART’s MacArthur station back up onto concrete walls and a line of freeway legs and overpasses. The community extends west of Martin Luther King and north and south of 40th Street. There are a smattering of small businesses and churches immediately behind BART on 40th and MLK but head a few blocks in either direction and you’ll soon see boarded-up storefronts, broken windows, and apartment houses pockmarked with crumbling paint. The buzz of commercial activity and heavy traffic along Telegraph Avenue lowers to the ghostly quiet of empty storefronts and weary corner liquor stores behind BART and the freeway. On the east side of Telegraph Avenue, homes sell for twice what they go for just a block to the west.

It was an entirely different picture in the 1950s, when construction of both the BART station and the 580/24 highway interchange had just begun. Madeline Wells, who still lives in the house where she was raised near the corner of Brockhurst and MLK, says she remembers when northwest Oakland was “a wonderful neighborhood.” But the large-scale train and road construction changed that.

“Thousands of houses and businesses were flattened to make room for BART and the highway,” says Wells, “and things have never been the same.”

The neighborhood was split more or less in two to make room for the tracks and the oval stanchions of 580 and 24. Bordering an overpass on MLK and 34th, a dirt and scrub-filled lot that rises to meet a BART wall has long been the source of low, wide swirls of dust that blow in the afternoon breeze.

“That was supposed to be park space, “ says Wells, shaking her head. “They promised us park space but they’ve been using it for construction machinery. There was supposed to be remuneration from the builders but the neighborhood has never seen any. “

“There were once thriving businesses here but the BART and freeway projects just cut many of them down,” she adds. “All there is now is housing, housing, housing, much of it Section 8, and a liquor store on every corner. It’s a neighborhood without services, just a dumping ground for public housing. We have the highest concentration of housing authority buildings in the city. There is lots of blight, and the abandoned housing here is used as shooting galleries. We need these building cleaned up. And we need businesses and libraries for the children. But merchants just won’t come to our neighborhoods.”

Much of the area was the focus of a notorious 60 Minutes report that aired in January of last year and pressed Mayor Jerry Brown to offer solutions to the high levels of crime and poverty and the deteriorating living and working spaces in northwest Oakland. Since the report aired, the city has painted curbs and lined streets with yellow dividing lines, added a police trailer to the neighborhood, and stressed code compliance for landlords—finally forcing them to upgrade and paint their neglected buildings. But neighborhood activists say this hardly adds up to a full-scale renovation of the neighborhood—the kind a transit village could have brought.

City Councilmember Jan Bruner admits that “when the freeway and BART stations were built it divided the community. All the concerns they have about the West Side are legitimate.”

But she says that at this point, the transit village—no matter how it’s designated—may not be able to do anything to solve the problem.

“I don’t know that the developers can ever incorporate the West Side into these plans,” she says. “To open the West Side will mean to open onto the freeway. And I don’t know if people would feel comfortable with a West Side entrance. It would mean a tunnel or a walkway and it’s doubtful that people would feel safe with that.”

Commuters now exit the MacArthur BART station without seeing much of the blight facing residents to its west. That’s because the station has walled off its west side: passengers face the tonier Piedmont and Temescal neighborhoods to the east when they come and go. Neighbors were hoping that part of any changes to the station would include tearing down the west-side wall or creating a west-side entrance that would facilitate new development on that side of Martin Luther King. In fact, the idea of developing the West Side had long been an integral part of the discussions surrounding the project—discussions that began at the community’s behest in a neighborhood meeting back in 1992. Patty Hirota, then a BART representative, remembers it well.

“All those years ago the Temescal neighbors group invited my boss to a meeting because they had heard about similar [transit village] projects across the country. At that first meeting it was clear that the city wanted to make this happen with the community. The same core community people kept with it and drew up a series of plans over the years. I have to hand it to the neighborhood activists. I’ve never seen a community come out in this way for a project.”

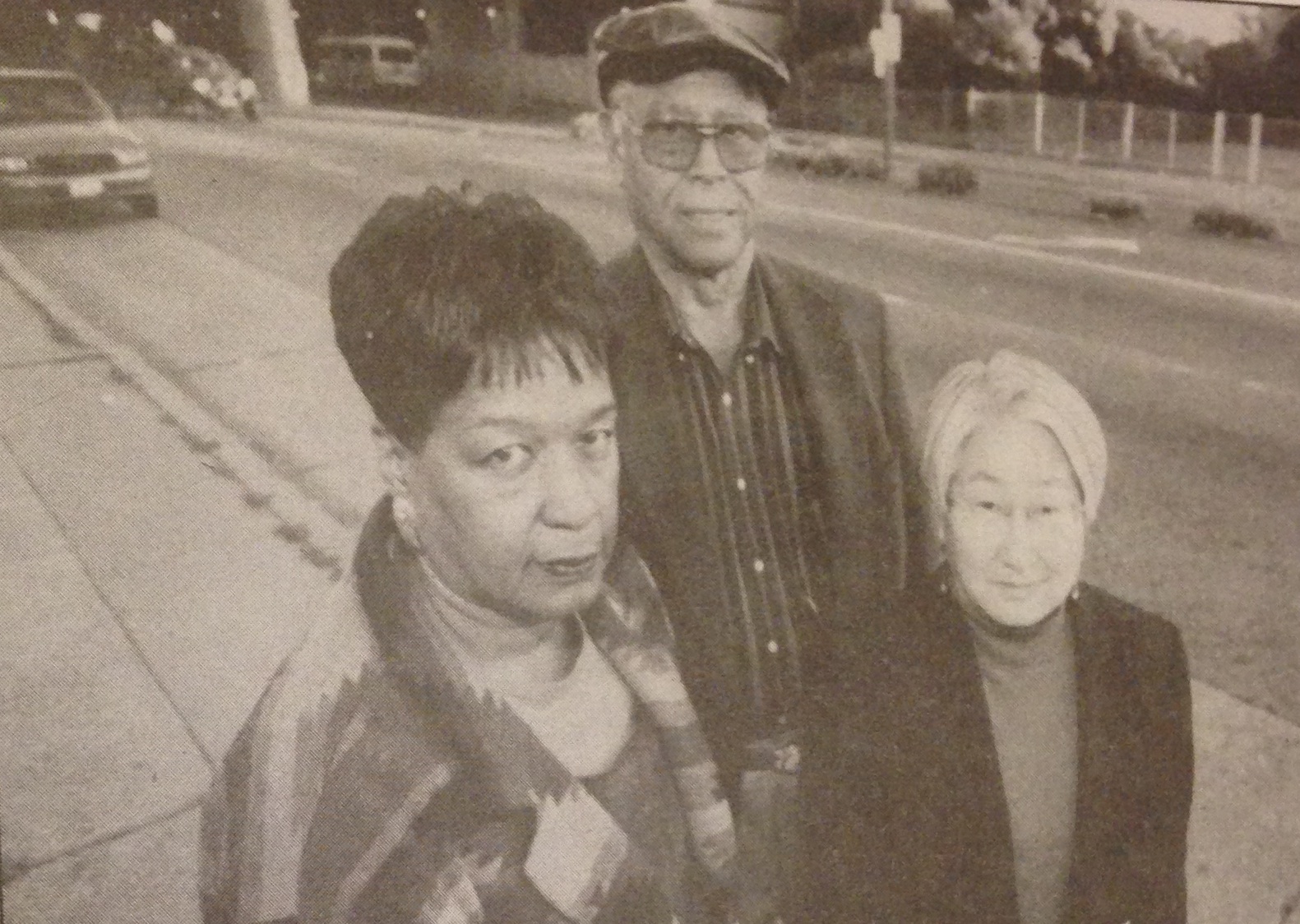

Earlier in the process, the community came up with “visioning plans” for the project, which emphasized West side development. According to Walter Miles, chair of what became the Citizens’ Planning Committee for BART, there was a proposal from the community to have a plaza that would encircle a new BART entrance between 40th and Apgar on MLK. But that proposal, like many others drawn up by the community and presented to the city and BART and developers over the years, was deemed “unleasible.” It is nowhere in the existing plans.

The current transit village plans position all of the development in and along the East Side, with the largest concentration in the existing parking lot. It’s understandable why the private developers who are largely funding this nearly $100 million project had little impetus to get on board with any West Side proposals, but activists say the city should have followed through on its original promises.

Miles says, “In that area, it’s like nobody’s fighting for you and that’s unfair. There’s not much talk about the West Side [in the presented plans], and as far as I’m concerned, it’ll be a disaster.”

Neighborhood activists like Lynne Horiuchi say they feel betrayed.

“Clearly, urging BART and the city to pay attention to the West Side in this project has not been a productive use of our time, “ Horiuchi says.

But city officials promise they’ll do something for the West Side neighborhood—just not the transit village.

“The mayor has a particular interest in seeing change happen in northwest Oakland, especially since the 60 Minutes piece happened,” says Erica Harrold, special assistant to Brown.

“Northwest Oakland has become a test case for the city, a place to see what can be done in terms of the improvement. If there is a way that the city can help the West Side, we will look into it.”

Councilmember Brunner wants to brainstorm with the community about other ideas for the neighborhood.

“The West Side may not be a part of this current project but I have been discussing [the neighborhood] in my meetings and once we know what we really want we can get closer to implementing it. One developer has expressed interest in the West Side but it’s too early to say whether that will come through.”

BART’s Hirota says that if West Side development is to happen, it should be initiated by the city—not by BART.

“The city owns two vacant parcels on the MLK side of the street, and these two parcels are the most logical starting point for some kind of revitalization. The BART station and its village is just not the best way to go. We’ve done our cross-feasability studies and the proposed [West Side] projects just won’t work.”

Horiuchi has a suggestion. She things that some of the redevelopment funds now slated for the transit village should go instead toward building a community center.

“I think we need to demand from Jane Bruner and [Councilmember] Nancy Nadel twenty percent of the redevelopment funds. I’m irritated with the city and BART for these seven years that we’ve put in. We have to do our own work now. We need to take these ideas that everyone has and start doing something we have control over.”

But Brunner points out that the city does not even have the money necessary to augment the current private investment in the transit village and she hopes state and federal sources will make up the $25 million difference. Still she, Hirota, and the developers are confident that the village will be begun, as is estimated, in 2003.

“ I think that this development team is really energized,” says Hirota. “They really want to make this happen.”

And so, apparently, does Jerry Brown.

“Mayor Brown is very much in favor of the village,” says Harrold. “He is an advocate for more transit villages and will be doing everything in his power to push both the [planned] Fruitvale and MacArthur villages. They appeal to his ‘elegant density’ notion.”

At last month’s press conference announcing the plans for the transit village, it was Brown who said he saw the village as a nice place to come and sip some wine. That’s a vision that Walter Miles would like to share.

“The city, the councilmembers, BART—we’ve always had a downright good partnership,” he says. Now if only that partnership could extend to the West Side. “People look at the West Side as low-income with dirty, nasty houses but it’s not only that,” Miles insists. “This community has character and could become another destination for Oakland. It makes a lot of sense to have a destination here.”

But Horiuchi says she won’t be holding her breath.

“In the end it doesn’t matter who is in office; it’s always the same thing,” she says. “They do not prioritize neighborhoods like this. It’s the way Oakland works.”

Recent Comments